Table of Contents

Table of Contents  Watch What I Do

Watch What I Do

Even though each PBD system has been written from scratch, requiring tedious coding, most of these prototypes share common components among which we find high-level events, a trace recording feature and a machine learning mechanism. The AIDE project tries to provide the developer with an application-independent Smalltalk-based environment for quickly implementing PBD-aware applications. In the next section we describe the AIDEWORKBENCH. Then we provide an overview of SPII, a general purpose object-oriented graphical editor built using this workbench, and gives examples of macros that can be created by demonstration. Finally, we discuss the way users can express their intentions in AIDE-based applications.

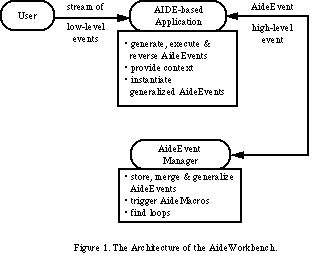

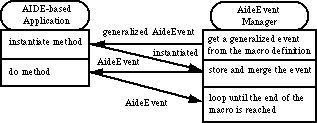

The AIDEWORKBENCH is designed to help software developers integrate advanced macro recording capabilities into their applications. To do so, the developer has to conform to our model of handling input by sending AideEvents (HLEs of a specific format) to the AideEvent Manager (an event manager including an inference engine).

When in teaching mode (i.e. a macro is being recorded), the AideEvent manager asks the AIDE-based application to enrich the event with contextual information i.e. information providing semantics to an HLE. Thus, in a word processor, the context associated with the command for selecting a word could contain the word itself, its position from the beginning and the end of the line, its style, etc. Then the AideEvent manager looks for loops and generalizes HLEs.

When in macro execution mode the AideEvent manager gets generalized AideEvents from the definition of the macro, asks the AIDE-based application to return an instantiation of such an event (a "regular" HLE obtained from the generalized one, which the application can then execute), stores it, and passes it to the AIDE-based application for execution.

Figure 1. The Architecture of the AideWorkbench.

The

dialog between an AIDE-based application and the AideEvent manager occurs by

the exchange of AideEvents. These, AideMacros, the AideEvent Manager and the

generalization process are described next.

For example, an AideEvent produced by a graphic editor might look like the following:

AideEvent new

name: 'Resize'; "event name"

sender: aGraphicEditor; "application which generated this event"

doArgs: #(4 9 94 79); "arguments used by the doMth (new frame)"

undoArgs: #(4 9 54 29); "arguments used by the undoMth (old frame)"

contextArgs: #(90 70 "contextual information provided by the

9/5 7/2); contextMth. Here, the new size and the ratio

between the new size and the old size"

doMth: #resizeDo:; "name of a method defined in the sender's

class in charge of performing the command.

In this example, resizing an object in

the window"

undoMth: #resizeUndo:; "name of a method defined in the sender's

class responsible for reversing the command.

In this case, restoring the object size"

generalizeMth: #resizeGen:; "name of a method defined in the sender's

class returning a generalized event by

coalescing it with another one (overrides the

default behavior)"

instantiateMth: #resizeInst:; "name of a method defined in the sender's

class returning an instantiation of a

generalized event"

contextMth: #resizeCxt:; "name of a method defined in the sender's

class filling the contextArgs slot"

mergeMth: #resizeMrg: "name of a method defined in the sender's

class that tries to merge this event

with previous ones"

In this example, the trigger method would test whether an object handle is clicked, and if so, would draw a rubber-band rectangle until the mouse button is released. Then, it would generate an HLE where the do/undo args slots would be filled, and send it to the AideEvent Manager for processing.

AideEvents act in a very simple fashion: when they receive messages from the AideEvent Manager like do, undo, fillContextArgs, generalize or instantiate, they just call the appropriate method of the application.

Moreover, AideEvents can be composed of other AideEvents, thus allowing multiple level undo/redo and adding robustness to the inference engine. This idea of aggregate HLEs came from David Kosbie's model (see Chapter 22). For example, successively moving the same object will create a "global move" AideEvent from the object's original position to its last position, and this global event will contain elementary move AideEvents. This allows the user to adjust the position of an object after moving it, without disturbing the inference engine which will only take into account the "global move" HLE. AideEvents are executed and merged with the higher-level AideEvent until a non-mergeable event arrives. The way events are merged to form higher-level events is described by a method referenced in the HLE mergeMth slot and defined in the sender's class. We use the same kind of regular expression rules as in [Kurlander 90]:

(select)*; select "merge select events"

(move)*; move "merge move events operating on the same objects"

(resize)*; resize "merge resize events operating on the same

x objects"

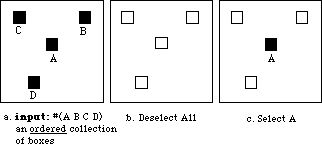

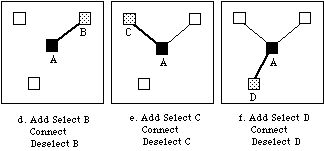

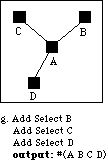

As in Lieberman's Mondrian system, the argument list is the ordered collection of the objects selected before invoking the macro. Then, the returned value consists of the selection list after the macro execution. Consequently it is possible to chain macros, arguments being passed through the selection list. Macros can call other macros and support recursion. When a macro is executed, generated AideEvents are passed to the AideEvent Manager which stores them as sub-events of the call-macro event (this means that during macro execution each AideEvent is merged with the call-macro HLE). Therefore, the results of a macro invocation can be undone by successively undoing the sub-events. To prevent double execution of a macro when redoing it, the sub-events are redone instead of the macro itself. We think that the capability to undo macros is crucial.

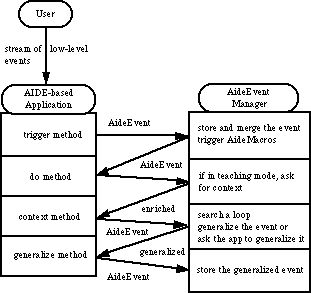

When the system is in teaching mode, it has the following additional steps (see Figure 2, which illustrates the dataflow between an AIDE-based application and the AideEvent Manager). First, the AideEvent Manager asks the application for contextual information (by calling the contextMth), receives back an enriched HLE, then searches loops and tries to generalize the HLE by comparing it with previously recorded HLEs (using a default generalization scheme or the event generalizeMth). Contextual information plays an important role because it helps the inference engine to guess the user's intentions. At last, the generalized HLE is stored in the macro definition and the AideEvent Manager waits for other incoming HLEs.

Figure 2. The dialog between an AIDE-based application and the AideEvent manager in teaching mode.

The

behavior of the event manager in macro execution mode is depicted

in Figure 3. Here, the AideEvent Manager picks up a generalized event from the

macro definition, sends it to the application for instantiation (by a

call to the instantiateMth which gives values to arguments), gets back a

"regular" AideEvent, stores it, and merges it with the call-macro HLE. Then it

passes the HLE again to the application for execution and picks up another

generalized event until the end of the macro is reached.

The

AideEvent Manager also supplies a VCR-like interface (see the figure at the

beginning of the chapter) in order to browse the user's trace and to undo/redo

commands across applications.

Much of the inference engine power resides in the way sequences are handled, which is inspired by Eager [Cypher 91a] and by Michalski's descriptors [Michalski 83]. A sequence is created by giving its two first values, then adding other values. For example, in the case of a linear descriptor, giving 4 and 9 as first and second values would create the linear sequence 4 to 9 by 5. Adding 14 as a third value would update this sequence to 4 to 14 by 5. Now if 15 was the fourth value, the sequence would become an increasing sequence from 4 to 15. For class sequences, the class attribute is a structured descriptor and the rule used is the climbing generalization tree rule. Moreover, sequences can be matched with other sequences, allowing generalization between two generalized macro traces. For instance, the sequence resulting from the match of a linear sequence with an increment of 2 and a linear sequence with an increment of 3 will be an increasing sequence. This last feature is used by the Give Another Example command.

The following shows how three resize HLEs as defined in the "AideEvents" section can be generalized:

event doArgs undoArgs contextArgs

resize #(4 9 94 79) #(4 9 54 29) #(90 70 9/5 7/2)

resize #(2 2 94 58) #(2 2 25 18) #(92 56 4 7/2)

resize #(6 3 94 73) #(6 3 50 23) #(88 70 2 7/2)

resize #(? ? 94 ?) #(? ? ? ?) #(? ? ? 7/2)

The generalized event is obtained by combining all of the arguments (doArgs, undoArgs and contextArgs) from the first event with the corresponding arguments from the second and third events. In this case, the generalized event interpretation is that the user resizes objects so that their bottom-right x coordinate equals 94 and their height is 7/2 times higher than the old one. A more complex example is given below.

Table 1 shows the user's trace which is a collection of enriched HLEs. Step 0 represents the selection list before recording the macro. For the other steps, we give the event name, the doArgs (name of the objects being manipulated) and the contextArgs. In the "context arguments" column, indexes "from beg." and "from end" refer to the position of the objects being selected or deselected, starting from the beginning or the end of the initial selection list (step 0). Other context arguments also exist for the select/deselect commands but they have been dropped because they were not significant in this example. Such arguments include object properties like class, position, color, size, etc. In the Star Macro, the criterion for selecting/deselecting objects was their index in the initial selection list, but because of the other context arguments, other criteria could have been objects whose name ends with ".bak" and/or whose color is black.

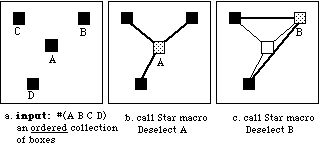

Figure 4. Star Macro: connects the first box in the selection to all the other boxes in the selection.

step figure event do context arguments

# # name args index in argument list

from beg. from end

0 4a #('A' 'B' 'C' 'D')

1 4b Deselect All #()

2 4c Select #('A') 1 4

3 4d Add Select #('B') 2 3

4 4d Connect #()

5 4d Deselect #('B') 2 3

6 4e Add Select #('C') 3 2

7 4e Connect #()

8 4e Deselect #('C') 3 2

9 4f Add Select #('D') 4 1

10 4f Connect #()

11 4f Deselect #('D') 4 1

12 4g Add Select #('B') 2 3

13 4g Add Select #('C') 3 2

14 4g Add Select #('D') 4 1

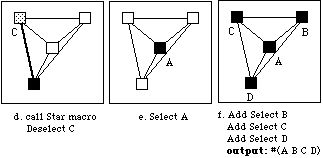

Table 2 illustrates the generalization of the enriched HLEs. The AideEvent Manager finds a first loop by coalescing steps 3/6/9, 4/7/10 and 5/8/11, and a second loop by coalescing steps 12/13/14. Each step is stored in a list corresponding to the trace, the loops being represented by sublists. In this case, the list is:

(DeselectAll Select (AddSelect Connect Deselect) (AddSelect))

In the latter loop (see the last line of Table 2), the generalization of the "from beg." context argument is that:

* objects from the second position up to the fourth in the selection list (when starting from the beginning) are being successively selected;

whereas the generalization of the "from end" argument is that:

* objects from the third position down to the first in the selection list (when starting from the end) are being successively selected.

By combining both generalized indexes when replaying this HLE, the AideEvent Manager will issue events selecting objects whose position goes from the second one to the last one in the selection list (starting from the beginning).

Table 2. Generalization of the Star Macro trace. "2 to lnArgLst 1" stands for "2 to length Argument List by 1".

steps event index in argument

list

coalesce name from beg. from end

d

1 Deselect

All

2 Select 1 to 1 4 to 4 by  const: 1

by 0 0

3 6 9 Add Select 2 to 4 3 to 1 by

const: 1

by 0 0

3 6 9 Add Select 2 to 4 3 to 1 by  2 to lnArgLst 1

by 1 -1

4 7 10 Connect

5 8 11 Deselect 2 to 4 3 to 1 by

2 to lnArgLst 1

by 1 -1

4 7 10 Connect

5 8 11 Deselect 2 to 4 3 to 1 by  2 to lnArgLst 1

by 1 -1

12 13 14 Add Select 2 to 4 3 to 1 by

2 to lnArgLst 1

by 1 -1

12 13 14 Add Select 2 to 4 3 to 1 by  2 to lnArgLst 1

by 1 -1

2 to lnArgLst 1

by 1 -1

The second example (Figure 5a-f) emphasizes how to create more complex macros by calling previously defined macros and passing arguments through the selection list. Here we want to create a complete graph by using the Star Macro and iterating over a set of boxes. This macro works on cases that do not have exactly 4 inputs.

Figure 5. The Complete Graph Macro creates a Complete Graph from a set of boxes.

1. Deselect All

2. Search

Select items 'verifying:'

'class' 'is' 'Rectangle'

from: 'outside the selection' "since the selection is empty,

Sort them by 'any order' search in the whole window"

3. Search

Select items 'verifying:'

'color' 'is' 'black'

from: 'inside the selection' "search should occur in the

Sort them by 'size' 'increasing x' already selected rectangles"

4. Deselect all elements but the first

one in the selection list

As we explained in the "AideMacros as user-defined AideEvents" section, the selection list before a macro creation represents the focus of interest. Much inference is done with respect to this list. This is a very convenient way to narrow the search space when looking for contextual information (in SPII, scanning objects is done in the selection list rather than in the whole window).

Intended users: non-programmers

Types of examples: Multiple examples

Program constructs: Parameterized procedures; loops, but no nested loops; no conditionals.

Table of Contents

Table of Contents  Watch What I Do

Watch What I Do