Table of Contents

Table of Contents  Watch What I Do

Watch What I Do

Just-in-time programming is the implementing of algorithms during task-time, the time when the user is actually trying to accomplish the task. It can be characterized by a situation with the following components:

It is worth emphasizing that the user's task could be from any domain (e.g. graphic drawing, scientific visualization, word processing, etc.) and that the algorithm originates with the user. Obviously, a user with more programming experience will be able to envision a more complex algorithm than a novice user. How the user comes up with the algorithm is not a concern. Also, no particular approach to solving the problem appears in the problem statement. Any programming system could conceivably be used for just-in-time programming, including C, PASCAL, keyboard macros, scripting languages, or PBD. PBD will probably be an important part of the more successful just-in-time programming systems, but the problem statement leaves open the possibility for other solutions.

Just-in-time programming research shares many of the motivations of other PBD research. Chief among these is that users often do repetitive or algorithmic subtasks that the computer could be doing. We call these subtasks potential computer subtasks and call these situations opportunities for new beneficial automation. Because automating can increase productivity and user satisfaction and at the same time reduce errors, one would expect the user to delegate potential computer subtasks to the computer. That users often do not take advantage of these opportunities motivates researching ways to improve the computer. Just-in-time programming research and PBD research assert that easier-to-use programming tools will allow users to take better advantage of opportunities for new beneficial automation.

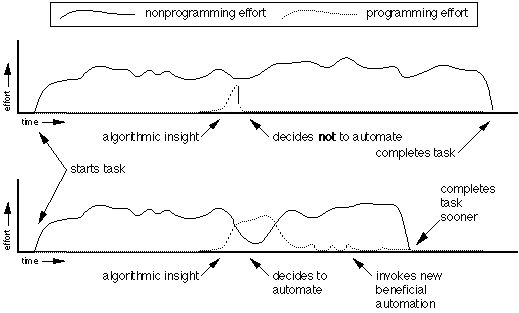

Just-in-time programming research, however, is focused on making programming easier for a specific cross section of situations. These situations are primarily defined by the user programming during task-time. In other words, the user attempts to write a program for a task that is already in progress. Figure 1 summarizes the relationship between task progress and the user's expenditure of effort. The expenditure of effort for just-in-time programming is shown separately from the other task related effort. The difficulty of just-in-time programming results from the spreading of the user's mental resources between two activities [Cypher 86]. Another difficulty is that the time spent programming contributes directly to total time between the start and completion of the task.

Figure 1. Two scenarios are shown of a user presented with an opportunity suitable for just-in-time programming. The intermixing of programming effort with other task related effort is shown for the second scenario where the user decides to apply just-in-time programming.

A classic example is when a document in one format has to be transformed to another format because of circumstances beyond the user's control. A small example of this happened to me when Symantec Corporation updated their Think C class library to version 1.1. Before version 1.1, rectangles were defined with 16-bit coordinates and in version 1.1 rectangles were defined with 32-bit coordinates. When I first compiled my software document with the new class library, type mismatch errors occurred where my software expected a variable representing a 16-bit rectangle. Many of these were simple assignment statements. The new class library included a utility function for converting 32-bit rectangles to 16-bit rectangles, so a typical fix involved changing a line of the form *inset=frame; to the form longToQDRect(&frame,inset);. Various other types of errors were found and fixed as well. The second time an assignment of a 32-bit rectangle to a 16-bit rectangle caused an error, I recalled that there were many such assignments throughout my program and concluded I would, in time, be transforming many lines from assignment statements into function calls. Each would differ only in the names of the variables and whether each variable was a pointer or not (i.e. preceded by a "*"). For the rest of this chapter, transforming one of these lines will be called the line transformation subtask.

So to break this situation down into the components of just-in-time programming:

{*}var1 = {*}var2;

to the form

longToQDRect({&}var2,{

(i.e. the line transformation subtask)

insert "longToQDRect("

if second variable name is not preceded by "*", insert "&"

insert second variable name

insert ","

if first variable name is not preceded by "*", insert "&"

insert first variable name

insert ")"

insert rest of line (the ";" and comments, if any)

delete original line.

For the line transformation subtask, data access meant obtaining the erroneous line's location and contents so that the algorithm could modify the part of the file that contained the line. Because of the way the compiler reported finding an erroneous line, this information clearly existed in the program editor. The compiler would automatically highlight each newly detected erroneous line in the program editor application, where I would normally edit the line manually. Because the program editor was a closed application, most of the programming systems on the computer were unable to access the required information. This was especially true of many versions of traditional programming languages like C and PASCAL, which typically can only access the file system and the user interface devices.

PBD helps eliminate the data and operator access obstacle both directly and indirectly. PBD indirectly eliminates the data and operator access obstacle simply by motivating research; PBD depends on data and operator access being possible and thus motivates the development of interapplication communication protocols like Apple Events. PBD takes a more direct role by greatly facilitating the use of low-level constructs in programs, which can sometimes allow data and operator access into otherwise closed applications. For example, the keyboard macro solution that appears shortly achieves operator access by simulating low-level user actions at the keyboard. Triggers (Chapter 17) shows how to extend this approach to data access using the pixels on the computer screen. PBD makes these solutions practical by providing the contextual clues and feedback that enable users to relate low-level data and operators to corresponding higher-level meanings.

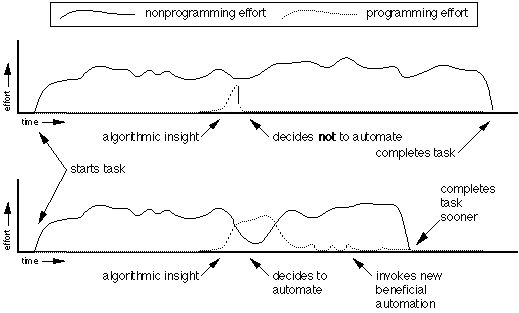

For the line transformation subtask, this obstacle never became an issue because the inaccessible data and operators obstacle alone prevented automating the subtask. But had data and operators been accessible, the effort of entering the algorithm would be a serious obstacle with many programming systems. For example, assume the program editor had a scripting language as extensive as the HyperTalk scripting language of HyperCard. Figure 2 shows a HyperTalk script that will automate the line transformation subtask, assuming that the line has been isolated in a variable. To make use of this HyperTalk script, the user would have to create it based on their algorithmic understanding of the subtask and physically enter it into the scripting system's editor. Just the physical effort of typing these 1185 characters (692 characters if comments and leading blanks are not included) is likely to undermine the benefits of automating. So while textual programming languages like HyperTalk are perfectly good programming languages for many purposes, they are often too verbose to be effective just-in-time programming languages.

Reducing this obstacle is PBD's forte. PBD helps reduce the effort of entering the algorithm by allowing users to enter algorithms using the same interface they would normally use to perform subtasks manually. This helps reduce both the physical effort and the mental effort because the user is often well practiced at using this interface. Since users would use the same interface to perform subtasks manually, the artifacts are already in short term memory and programming with them is likely to be less distracting than with a textual programming language. The effort of entering the algorithm is also reduced because user interfaces are usually optimized to the task.

Figure 2. A HyperTalk function that automates the line transformation subtask assuming the line has been isolated in a variable

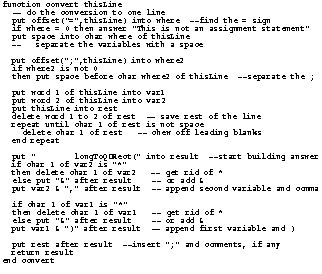

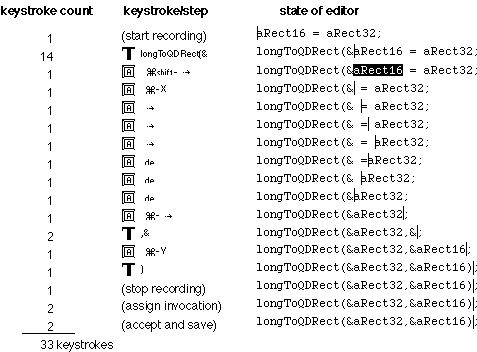

For

a simple example of how PBD can dramatically reduce the effort of entering an

algorithm, consider the following partial solution to the line transformation

subtask. If the user first places the cursor to the left of the first variable

in the line to be transformed, and if neither variable is a pointer, then the

QuicKeys macro shown in Figure 3 will transform the line as required. The

macro also assumes that exactly three characters (" = ") separate the two

variable names. Only the 33 keypresses shown in Figure 3 are required to

implement the macro. The visual feedback of the editor also helps reduce the

mental effort by showing intermediate results as the user demonstrates

the low-level keystrokes that accomplish the subtask.

Limited

computational generality is the reason why the virtues of the keyboard macro

were demonstrated by only partially automating the line transformation subtask.

The subtask requires conditional logic to decide whether each variable is a

pointer or not, as specified in the algorithm. Most keyboard macros only record

straight-line algorithms and are not able to fully automate this subtask.

Unfortunately, computational generality is not one of PBD's strengths. Dan Halbert recognized this when implementing SmallStar and concluded that control structures were better created by editing a static representation of the program than by demonstration (Chapter 5). Others have used inference to generalize straight-line demonstrations into procedures that have control structures. Allen Cypher's Eager (Chapter 9) and Brad Myers' Peridot (Chapter 6) used domain knowledge to infer procedures with control structures solely from straight-line demonstrations. The computational generalities of these systems, however, are limited by domain knowledge.

In order for a PBD system to be widely effective for just-in-time programming, it will have to be integrated with other techniques to give full computational generality. Interesting directions include giving separate examples for each path of the algorithm as in Henry Lieberman's Tinker (Chapter 2), or a combination of multiple demonstrations, inferencing, and special instructions from the user as in David Maulsby's Metamouse (Chapter 7).

The line transformation subtask is typical of many subtasks suitable for just-in-time programming in that the benefit gained from each invocation is small. One popular invocation strategy, especially with keyboard macros, is a specially assigned keypress. One keypress to transform one of the lines is a satisfactory solution, and certainly does not present an obstacle if just the physical effort is considered. The effort sometimes becomes an obstacle when complexities of the task-time situation plus the effort to remember and properly apply the automation strain the user's attention. Keystrokes can become difficult to remember because most simple keystrokes are already claimed by application programs. Often only convoluted keystrokes like control-option-"L" are available. If several opportunities appropriate for just-in-time programming arise, keeping straight which keystroke goes with which automation can be a challenge.

There are situations where even minimizing the physical effort can be particularly crucial towards making automation beneficial. Consider the feature on many word processors that allows a user to select a word simply by double-clicking on it. The word processor automatically does the tedious subtask of extending the selection out to the word boundaries. Identifying these word boundaries manually is a simple subtask, so not much benefit is received each time the feature is used. However, words are selected so commonly that, over time, the feature is very beneficial. Another invocation strategy could easily undermine this benefit. For example, even requiring the user to click on the word and then select the feature from a pull-down menu could require too much effort.

Just-in-time programming systems should allow the user to choose among various invocation strategies. Standard invocations such as menu selections and keypresses should be supported. The ability to create more refined invocations, like double-clicking on an object to apply some automation to it, would be important for making some highly interactive automations worth creating. PBD techniques could possibly be used to demonstrate that the automation should be invoked whenever the user starts to perform the subtask. David Maulsby's Turvy (Chapter 11) and Metamouse (Chapter 7) give hints as to how this might work. See Chapter 21 for further discussion of invocation techniques.

Consider the risks of automating the line transformation subtask. There are many possible scenarios. In the best case the algorithm could have been entered almost effortlessly, and as each occurrence of a line needing the simple transformation was flagged by the compiler, I could have easily invoked the algorithm somehow. To my surprise, perhaps more chances to use the new automation occurred than were anticipated, making the automation pay off more than expected.

But there are many other possible scenarios. The algorithm could have taken a long time to enter, perhaps because some special purpose function had to be looked up in a manual. A mistake in the implementation might have caused the new (not beneficial) automation to destroy part of the source file, perhaps too quickly to be noticed. Limited data access could have turned the simple algorithm into one that was impossible to implement. I was not sure exactly how many more assignments of 32-bit rectangles to 16-bit rectangles were left in my software project, and thus there may have been too few to make the programming effort worthwhile. Unforeseen special cases may have made the envisioned algorithm simply wrong.

Risk was the main reason I chose not to automate the line transformation subtask. The partial solution using keyboard macros was the only solution worth considering because it was the only one that had ready data and operator access. In the past, my attempts to use keyboard macros have often been thwarted by unforeseen special cases, the difficulty of accommodating special cases into an already existing macro, and the uncontrollable speed of macros that makes it difficult to verify that the macro works correctly. In retrospect, a keyboard macro would have been worthwhile and would have prevented a few recompiles caused by typos in my manual transformation of the lines. However, at the time, the apparent risks convinced me to play it safe and transform the lines manually.

Essentially the user's risk is that the manual method might be more effective than implementing the algorithm. Therefore, an approach to reducing risk is to allow the user to pursue both alternatives in parallel. In theory, the risk of attempting to automate the subtask would be eliminated because if unforeseen difficulties make the programming effort ineffective, then the user could fall back on the manual method already underway.

In practice, this approach would probably not eliminate risk, but it could reduce risk greatly. PBD could play a large part in realizing this approach because it allows the user to implement algorithms by demonstrating on their actual task data. In other words, the user can be programming and manually accomplishing the subtask simultaneously. For example, recording the keyboard macro in figure 3 actually transforms one of the lines, so progress towards completing the overall task is hindered minimally.

This technique has its greatest potential when mixed with history-based techniques. For example, Allen Cypher's Eager (Chapter 9) records the user's actions into an event history. When Eager detects the user doing repetitive actions, it indicates this to the user by highlighting what it expects the user to select next. For certain classes of algorithms, the user can implement an algorithm at almost no risk because the user takes no special actions. The decision of whether to invoke the algorithm still involves some risk because the exact behavior of some algorithms is difficult to predict. Therefore additional techniques such as undo and slow motion execution will have to be extended and refined.

The five obstacles outline multiple avenues of research. The effort of entering algorithms and limited computational generality encourage researching ways to balance PBD with techniques that ensure full Turing-complete computational generality. The effort of invoking the algorithm encourages designing flexible invocation schemes that will not interfere with the existing user interfaces of applications. Inaccessible data and operators encourages establishing new communication protocols or finding ways to take advantage of existing protocols. Risk encourages researching PBD techniques that allow the user to flirt with the possibility of automating a subtask without hindering their progress on the overlying task. Researching ways to overcome the obstacles individually gives the freedom to investigate and evaluate these and other more speculative research directions.

When it comes time to produce practical just-in-time programming systems, all of these obstacles must be addressed simultaneously. If compromises need to be made among which of the five obstacles to address, eliminating risk should receive the highest priority. If users cannot accurately assess the risks, the programming system will fail for lack of use. The goal should be to create a programming system where users can know that in the worst case, attempting just-in-time programming will not hinder progress towards completing the task. Then users will be able to confidently use the full extent of the programming system to profit from their algorithmic insights.

PBD promises to play an important part in making effective just-in-time programming a reality. It is the most promising research area for addressing risk and the effort of entering the algorithm. It plays supportive roles with the effort of invoking the algorithm and the inaccessible data and operators. The open question is whether PBD combined appropriately with other techniques can produce a programming system that eliminates all the obstacles.

Table of Contents

Table of Contents  Watch What I Do

Watch What I Do